Hip and groin pain can significantly affect daily activities such as walking, getting in and out of a car, or squatting. Many people tend to push through mild discomfort, believing it might resolve on its own. When the pain becomes persistent or worsens, it can be concerning and may point to an underlying issue. One common cause for hip-related discomfort is Hip Impingement (FAI), a mechanical problem in the hip joint that can lead to pain, reduced mobility, and eventual cartilage damage if left unaddressed.

Hip Impingement (FAI) often surfaces in younger, active adults and athletes, but it can appear in individuals of various ages. Understanding how this condition develops, what its typical signs are, and how it can be treated is essential for preventing long-term damage and preserving quality of life. Below is a detailed exploration of Hip Impingement (FAI), aimed at providing in-depth, patient-friendly information on its anatomy, causes, symptoms, diagnostic tests, management strategies, and outcomes.

What Is Hip Impingement (FAI)?

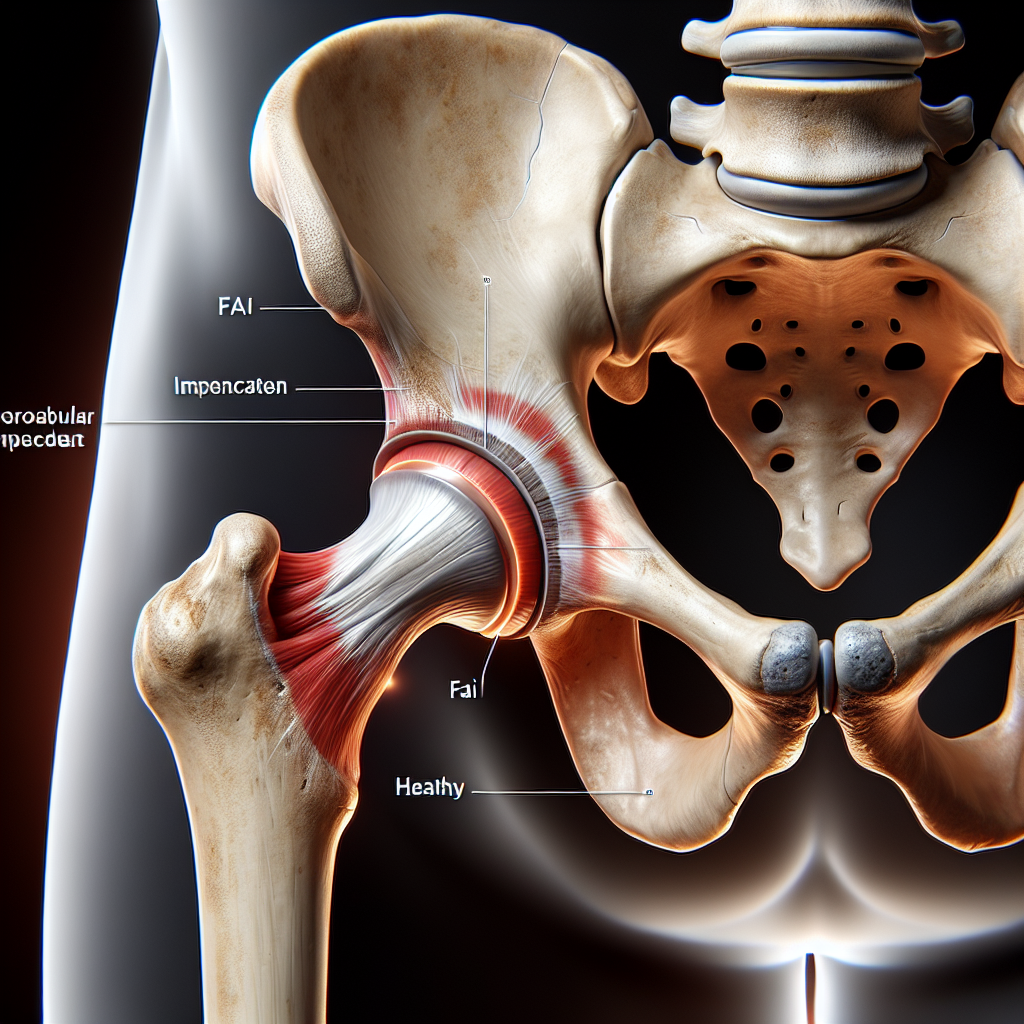

Hip Impingement (FAI) is a condition where the ball and socket of the hip joint do not fit together perfectly, resulting in abnormal contact between the femoral head (the “ball” of the hip) and the acetabulum (the “socket”). This mismatch can cause the joint surfaces to rub or pinch abnormally during certain movements or positions, such as deep hip flexion or twisting motions. Over time, this irregular contact can lead to pain, inflammation, damage to the cartilage, and restrictions in normal joint function.

There are generally three main forms of Hip Impingement (FAI):

- Cam Impingement: A bony overgrowth on the femoral head or neck. The sphere-like shape of the ball is no longer perfectly round, causing it to pinch against the socket.

- Pincer Impingement: An overgrowth of the acetabulum, leading to excessive coverage of the femoral head. The rim of the socket can then impinge on the femoral neck.

- Combined (Cam and Pincer): A mix of both cam and pincer impingement, which is relatively common and involves aspects of each deformity.

Key Points

- Hip Impingement (FAI) happens when the femoral head and acetabulum make frequent, abnormal contact.

- Chronic rubbing can lead to wear and tear in the joint, causing labral tears and cartilage damage.

- Early diagnosis and management can help preserve joint function and delay or prevent more severe issues such as osteoarthritis.

Anatomy of the Hip Impingement (FAI)

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint formed by the femoral head (top of the thigh bone) and the acetabulum (part of the pelvic bone). Smooth articular cartilage covers both surfaces, allowing near-frictionless movement. Another important structure within the joint is the labrum, a ring of cartilage along the rim of the acetabulum. The labrum contributes to hip stability and helps seal the joint.

In Hip Impingement (FAI), structural deviations within these anatomical components create a mechanical block during movement. Small changes in bone shape can lead to more stress being placed on the labrum or cartilage:

- Femoral Neck and Head: When a cam deformity is present, it alters the round contour of the femoral head, causing it to jam into the socket with activities involving hip flexion or rotation.

- Acetabular Rim: A pincer deformity increases the coverage of the femoral head by the socket. During certain movements, the overhanging rim compresses the femoral head and labrum.

Supporting Structures to Consider

- Joint Capsule: A strong fibrous structure that encloses the joint.

- Ligaments: The iliofemoral, ischiofemoral, and pubofemoral ligaments assist in stabilizing the hip by limiting excessive motion.

- Muscles and Tendons: The surrounding muscles (e.g., hip flexors, extensors, abductors) generate movement and provide additional stability. Repetitive pinching or mechanical stress from Hip Impingement (FAI) can also lead to compensatory movements in these muscles.

Understanding these elements helps us see why even minor structural abnormalities can cause major functional issues in Hip Impingement (FAI). Early identification of any bony irregularities can keep the condition from progressing to a stage where cartilage and labral damage become severe.

What causes Hip Impingement (FAI)?

Hip Impingement (FAI) develops primarily due to abnormal bone formations around the hip’s ball and socket. The exact reasons for these formations are not fully understood, but both genetic and lifestyle factors can play a part.

Sometimes individuals are born with subtle variations in hip anatomy that remain undetected until they start engaging in activities that stress the hips, such as competitive sports. Certain sports and training routines require deep squats, rapid pivoting, or repeated hip flexion, which may accelerate or aggravate underlying structural issues.

Here are common factors that may contribute to Hip Impingement (FAI):

- Genetic Predisposition: Family history of hip deformities can increase the likelihood of developing cam or pincer lesions.

- High-Impact Sports: Repeated stress from sports like football, hockey, soccer, or dance can lead to bony overgrowth in response to repetitive loading.

- Growth Plate Injuries: Adolescent hip injuries that affect growth plates might result in an altered shape of the femoral head or neck.

- Structural Changes Over Time: Even normal aging can alter hip bone structure slightly, though typically, Hip Impingement (FAI) is more frequent in younger or middle-aged adults who are physically active.

Contributing Factors to Progression

- Inadequate warm-up before exercises or competitive play.

- Poor biomechanical alignment and movement patterns.

- Weak or tight hip muscles that strain the joint excessively.

- Delaying treatment for early signs of hip pain, which can worsen impingement over time.

What are the Symptoms of Hip Impingement (FAI)?

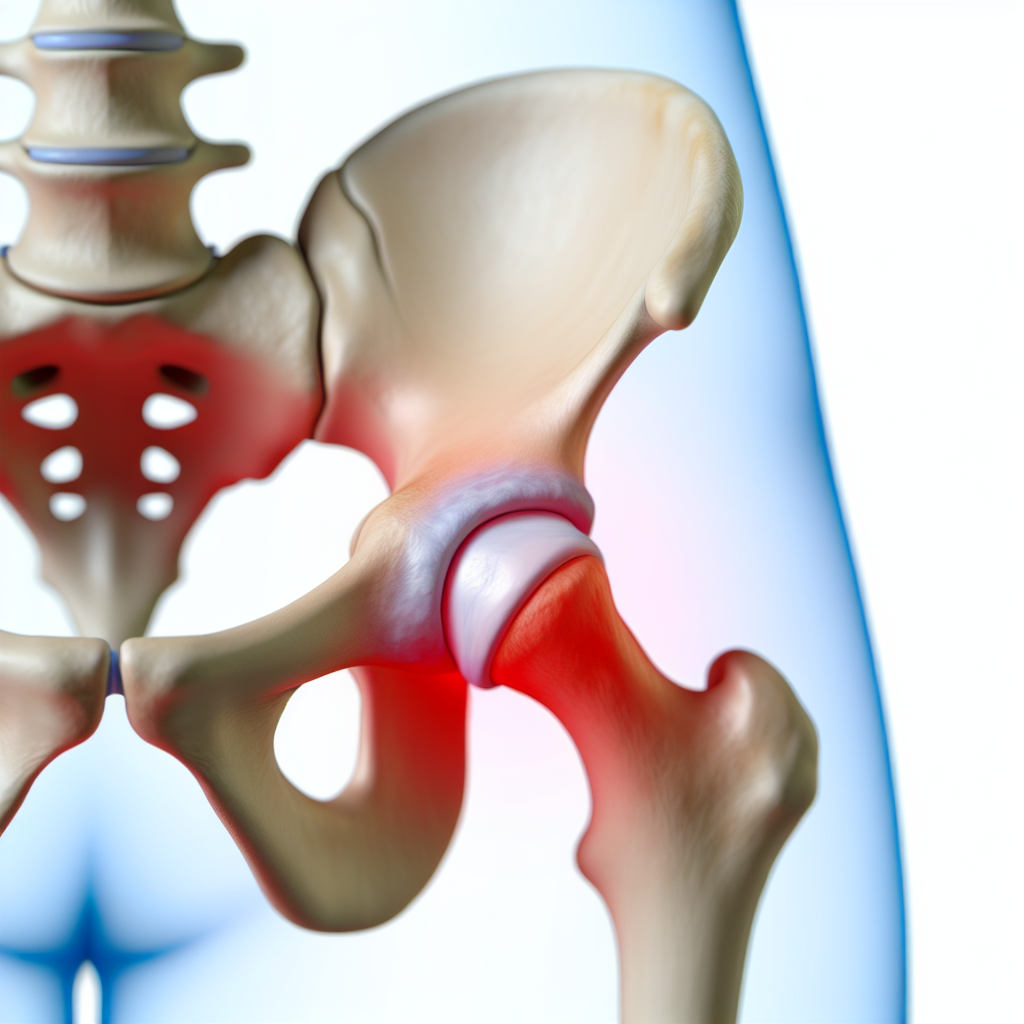

People with Hip Impingement (FAI) often notice stiffness or deep ache in the front of the hip or groin region. This pain typically arises after prolonged sitting, activities involving deep flexion (like squatting), or rotating the hip inwards. Because the labrum and cartilage can be irritated or damaged, the discomfort may be sharp at times, particularly with sudden hip movements.

Common symptoms include:

- Groin Pain: A deep groin ache or sharp pain felt during or after athletic activities.

- Clicking or Catching: Sensations of the hip getting “stuck” or making a clicking noise when moving in certain directions.

- Reduced Range of Motion: Trouble bending the hip fully or rotating outward/inward without pain or stiffness.

- Pain with Sitting: Prolonged sitting, especially on low seats or in cramped positions, can trigger discomfort upon standing.

Not everyone will experience all of these signs, and symptom severity can vary. Some people only have minor discomfort that flares up after intense activity. In contrast, others may develop persistent issues that hinder everyday tasks. Identifying these indicators is vital for prompt diagnosis and early management of Hip Impingement (FAI).

Special test of Hip Impingement (FAI)

Several physical examination tests help detect Hip Impingement (FAI). These tests aim to reproduce the hip pain by placing the joint in specific positions that compress the labrum or cause contact between bony deformities. Below is a list of commonly used tests, along with brief descriptions of how they are performed.

FADIR (Flexion, ADduction, Internal Rotation) Test

- The person lies on their back.

- The hip is flexed to about 90 degrees, then gently moved into adduction (toward the midline) and internal rotation (turning the thigh inward).

- A positive test occurs if this maneuver provokes or recreates the familiar hip/groin pain.

FABER (Flexion, ABduction, External Rotation) Test

- With the person on their back, the hip is placed in flexion, abduction (away from the midline), and external rotation (turning the thigh outward) so the foot rests above the knee of the opposite leg.

- The examiner gently applies downward pressure on the bent knee.

- Pain in the hip or groin region may suggest Hip Impingement (FAI), but this test can also indicate other hip or sacroiliac joint problems.

Thomas Test

- The person lies supine on a table or examination bed.

- One knee is held to the chest to flatten the lumbar spine.

- If the opposite leg lifts off the table instead of remaining flat, it could indicate tight hip flexors. Though primarily used to assess hip flexor tightness, discomfort during the test can also shed light on possible impingement.

Scour Test

- The hip is flexed and then passively moved in a circular or arcing motion while applying mild axial pressure.

- Pain or catching sensations may occur if there is labral or articular surface irritation consistent with Hip Impingement (FAI).

Resisted Straight Leg Raise

- The person lifts one leg straight up off the table while lying on their back.

- The examiner applies gentle downward pressure to gauge hip strength and pain response.

- If groin discomfort arises, it might indicate intra-articular pathology such as Hip Impingement (FAI) or labral tear.

It is crucial to interpret these tests in conjunction with imaging studies like X-rays, MRIs, or CT scans. A definitive diagnosis often requires correlating the clinical exam with imaging to determine the presence and extent of any cam or pincer deformities.

How do we Treat Hip Impingement (FAI)

Management of Hip Impingement (FAI) typically depends on how severe the structural changes and symptoms are. For many individuals, conservative (non-surgical) methods are highly effective at reducing pain, improving range of motion, and preventing further joint damage.

Hip Impingement (FAI) Treatment Approaches

Conservative Management

- Activity Modification: Adjusting or temporarily avoiding activities that aggravate hip pain, such as deep squats, can help reduce inflammation.

- Physical Therapy: Exercises that focus on muscle strengthening, flexibility, and restoring hip mechanics are central to treatment. Targeted stretches aim to relieve tension in tight areas, while strengthening exercises help stabilize the hip joint.

- Manual Therapy: Joint mobilizations, soft tissue release, and other hands-on techniques can alleviate tightness and improve hip range of motion.

- Anti-inflammatory Measures: Cold therapy, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and occasional injections of corticosteroids into the joint can reduce acute pain and swelling.

- Hip Joint Mobilization Exercises: Carefully guided exercises to restore normal arthrokinematics within the hip can enhance movement quality.

Surgical Management If conservative approaches do not provide relief or if imaging shows significant deformities or labral damage, surgery may be necessary. Hip arthroscopy is a minimally invasive procedure that allows the surgeon to reshape the femoral head, repair the labrum, or address pincer overgrowth on the acetabulum. By correcting the bony abnormalities, surgeons aim to minimize ongoing damage and improve joint function.

Although surgery can be successful for many, post-operative rehabilitation is essential to ensure an optimal outcome. Physical therapy after surgery will typically include:

- Gradual progression in weight-bearing.

- Range-of-motion exercises to prevent stiffness.

- Strengthening of core and hip stabilizers.

- Gradual return to sport-specific or functional movements.

Hip Impingement (FAI) Differential Diagnosis

Because hip and groin pain can originate from multiple structures, ruling out other conditions is crucial. The following are some common differentials:

Hip Osteoarthritis

While Hip Impingement (FAI) can lead to early degenerative changes, pre-existing osteoarthritis or advanced joint degeneration might be the true source of pain. Radiographic studies help reveal joint space narrowing, bone spurs, and cartilage wear that point to osteoarthritis.

Labral Tear

A tear in the cartilaginous ring (labrum) can present similarly, causing groin pain, clicking, or catching sensations. Though labral tears often occur together with Hip Impingement (FAI), they can also arise independently from trauma or repetitive stress.

Muscle Strains and Tendinopathies

Hip flexor strain, adductor tendonitis, or gluteal tendinopathy can all create localized pain around the hip and groin. However, these soft tissue injuries typically involve tenderness upon palpation of the affected muscles or tendons, distinguishing them from Hip Impingement (FAI).

Bursitis

Inflammation of the trochanteric or iliopsoas bursa may mimic Hip Impingement (FAI) pain. Bursitis often presents with pinpoint tenderness over the bursa and may worsen with direct pressure (e.g., lying on the affected side).

Lumbar Spine Pathologies

Referred pain from the lower back or sacroiliac joint can present similarly to Hip Impingement (FAI). A careful clinical examination can differentiate spinal issues from intra-articular hip pathologies.

Arriving at the correct diagnosis is a team effort, often involving cooperation between physiotherapists, orthopedic specialists, and radiologists. It is essential to correctly identify underlying causes to guide the most effective treatment plan.

Hip Impingement (FAI) Prognosis and Expectations

With early diagnosis and well-structured treatment, the long-term outlook for Hip Impingement (FAI) can be favorable. Conservative management can significantly reduce symptoms, enabling individuals to return to regular activities or sports in a matter of weeks to months. Factors that influence prognosis include the extent of bony deformities, the presence of labral or cartilage damage, and individual compliance with rehabilitation.

Key Prognostic Factors

- Severity of Structural Changes: Minor deformities are often easier to manage and respond more quickly to conservative measures.

- Timing of Intervention: Prompt detection and treatment can halt or slow cartilage damage, preserving joint health longer.

- Physical Therapy Adherence: Commitment to exercise programs ensures better muscle balance, improved range of motion, and effective stress distribution across the hip joint.

- Lifestyle Adjustments: Modifying high-risk activities, managing body weight, and addressing biomechanical imbalances can all help sustain progress made during rehabilitation.

Post-surgical outcomes can also be good, especially if the procedure successfully reshapes the joint and repairs labral damage. Nonetheless, full recovery can take several months, and diligent participation in post-operative rehabilitation makes a significant difference in returning to optimal function.

Maintaining open communication with healthcare providers, setting realistic goals, and performing routine follow-up evaluations all contribute to achieving the best results. In many cases, individuals with Hip Impingement (FAI) can resume active lifestyles without pain, provided they respect the joint’s limits and stay proactive about rehabilitation and maintenance exercises.